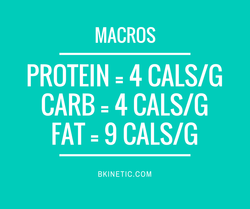

Macronutrients are the building blocks of our food. They include protein, carbohydrates, and fats. (I’ve included fiber below as well, as it is an important part of a healthy diet (it fits in under the carbohydrate umbrella)).

Once you have gotten the hang of including more and more healthy, minimally processed foods in your diet, you may want to think about tracking your macros. This helps to ensure that you are getting in an optimal amount of each macronutrient to support your activities, body type, and goals. The easiest way I have found is to use a smartphone app like Lose It or My Fitness Pal.

It can be really eye-opening to see just what and how much you are eating each day. Even though I like eating meat, eggs, and protein bars, I still struggle to get in enough protein each day. So tracking my intake every once in a while or when I’m in fat loss mode really helps there, and makes me more aware of proper portion sizes.

Let’s get into the nitty-gritty of macros:

PROTEIN

Protein, found in a variety of foods like beef, pork, fish, poultry, beans, eggs, dairy, and supplements (powders and bars) contains amino acids, which are the building blocks of muscle. Amino acids are responsible for hormones, enzymes, immune chemicals (immunoglobulins and antibodies), and transportation of proteins.

It also has a high TEF (thermic effect of food), meaning that it takes the body more energy (calories) to break it down than other macronutrients.

There is quite a bit of controversy as to the required or best amount of protein intake. Some argue that we already consume too much protein, while others say the opposite. The US Recommended Daily Allowance for protein is listed at only 0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight (1 kg = 2.2 lb). According to that guideline, someone who’s 150 lbs. would only “need” 55 grams of protein per day. But keep in mind that these guidelines are merely the amount needed to prevent a deficiency in sedentary, relatively healthy individuals. It doesn’t take into account an active lifestyle, nor optimal performance nor aesthetics.

Protein provides a satiety effect that can help you eat less overall, and studies have found that people on diets high in protein (25-35% of daily calories) tend to burn more fat and lose less muscle than people on diets with intakes of 15% or less. A more optimal protein intake is 1.4-2.0 grams per kilogram of body mass (for example, 95-135 grams for a 150-lb. individual)

¹.Another well-known guideline is 1 gram per pound of body weight or lean muscle mass (if the individual is very overweight or obese). A high intake is especially crucial when training with a high intensity or cutting calories and/or carbs. Stuart Phillips, PhD, a professor of kinesiology and researcher at McMaster University in Ontario, Canada has found in his studies that this amount seems to be the most beneficial for calorie-restricted dieters.

A high protein intake helps spare muscle when cutting calories².

A common myth is that excess protein is stored as fat. Let’s get this straight: an excess of any macronutrient can cause it to be stored as fat, but there is nothing inherently special about protein in that regard. As long as your total daily calories are in check and your hormones balanced, a high intake of protein will not pose a threat to your waistline.

Another myth is that diets high in protein are dangerous for your kidneys. This fallacy comes from studies that showed that a high protein intake worsened the function of the kidneys in individuals with pre-existing renal disease or failure. Consequent studies found that a high protein intake in people with healthy kidneys is perfectly safe. One study found that a high protein intake of 33% of total daily calories in overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes (a group at high risk of kidney failure) did not show any differences in blood lipids or kidney function measures when compared to the low protein group (19% of daily calories). Add in resistance training over 16 weeks, and the high-protein group lost more body fat and reduced their waistline more than the low-protein group³.

For more info, check out Layne Norton’s website, biolayne.com. He has a PhD in Nutritional Sciences and has studied protein synthesis extensively.

Carbs are not evil. They are individual. Some people do best on a higher carb diet, such as those who compete in endurance sports or have an ectomorph body type (naturally thin, hard time gaining weight). Some see better results with a low-carb approach, while most seem to thrive on something in the middle. It’s all about experimenting and seeing what works best for YOU. I typically will start clients at a more moderate level of carbs (usually around 40% of total calories) and fat (25-30% of total calories) depending on their body type and activity level, and go from there.

Carb intake should be inversely proportional to fat intake. When fat is high, carbs should be lower; if fat is low, carbs should be higher.

Carbs that have a slower rate of absorption and digestion are best for satiety, keeping blood sugar steady, and improving body composition. These include fiberous veggies and fruit. Carbs that are digested more quickly are more beneficial when consumed around a workout, including starches (like potatoes and beans), higher-sugar fruits, and whole grains. If I want to indulge in food that is higher in sugar or is a refined carb source (froyo, pizza, etc.), I try to save it for after a strength workout, when my muscles are more likely to use it for building muscle rather than storing it as fat (keeping my overall calories and macros in check, of course).

FIBER

Fiber increases satiety, improves intestinal mobility (bowel movements), helps reduce cholesterol, and reduces risk of colon cancer. Good sources of fiber are veggies, fruit, oats, beans, peas, flaxseed, seeds, nuts, and whole grain products.

Aim for 25-35 grams per day from produce and whole grain carb sources. Gradually increase your intake instead of adding a bunch in all at once to minimize gastrointestinal distress.

FAT

Dietary fat has a host of benefits — managing inflammation, creating a favorable hormonal balance, and supporting healthy immune function. It’s an energy source, helps transport fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K, (which is why you want to have a small amount of fat in your salads — to help the absorption of those vitamins), and provides two essential fatty acids that the body can’t make — linoleic acid and linolenic acid.

Healthy sources include fatty fish (salmon or sardines), olive oil, coconut oil, avocado, nuts, natural nut butter, and butter from grassfed cows.

Omega-3 fatty acids are important to include in a healthy diet, whether through food (fish) and/or in supplement form. They increase insulin sensitivity, help messages from neurochemicals like serotonin be transmitted more easily, enhances cardiovascular function and nervous system function, and aid immune health.

Finding the optimal ratio of macronutrients for you is a process of trial-and-error. Nutrition is so individual. There is no one-size-fits-all approach that works for everyone. So start at a moderate place for 2+ weeks and track what works and what doesn’t. Experiment, but only change one thing at a time so that you can know for sure what is doing what. It takes time, but eventually you’ll get to a place where it feels more effortless and it’ll be a way of eating that you can see yourself still doing in five years.

I hope this introduction to macros has been helpful. If you have any questions, please be sure to hit me up on my Facebook page.